Understanding science: Knowledge is tentative, self-correcting and open to revisions

Scientific conclusions are tentative, and always open to revision as new data comes in (Dunn, 2009). This is doubly true when studying something as mutable and complex as human psychology. Results that were once valid may become invalid as technological and cultural changes occur.

An intervention that is successful in one organization may not be have an effect in another organization. Given this reality, you will never find evidence-based recommendations that are guaranteed to be successful or universally applicable to all situations.

The constantly-evolving, tentative nature of science can be frustrating if you are in search of a clear-cut answer to an organizational problem. It is vital, then, that adopt a mindset that embraces ongoing research. Science cannot promise a resolved, categorical answer to a question, or promise that a strategy is the “best”.

It can, however, document the situations and organizations in which an intervention worked, and provide an explanation of why the intervention may have worked (Paul, 1991). This information can be used to help you select strategies that fit your organization and its needs.

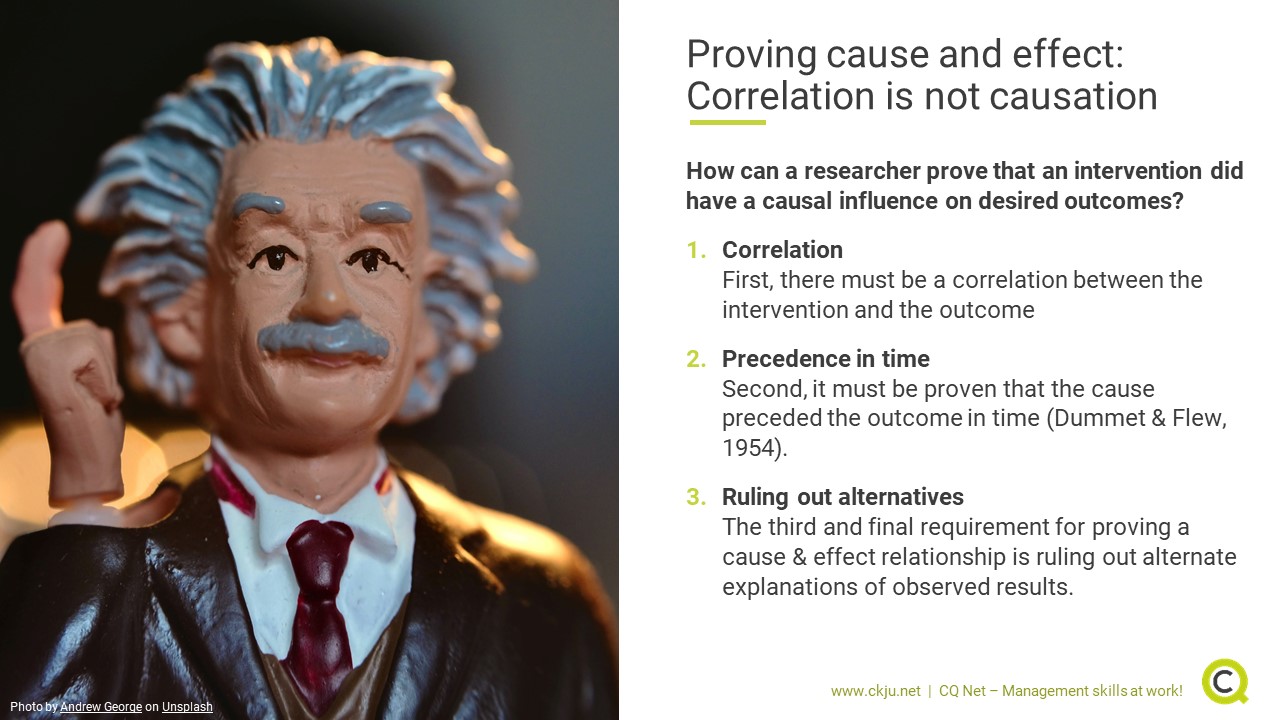

Proving cause and effect: Correlation is not causation

You are probably familiar with the adage correlation is not causation. In other words, finding an association between two events is not sufficient proof that one event caused the other. Within an organization, it can be very difficult to establish that a favorable outcome occurred because of an intervention, and not due to other factors, such as personnel changes, economic and political events, or even random chance.

How can a researcher prove that an intervention did have a causal influence on desired outcomes? The three conditions correlation, precedence in time and ruling out alternatives must be met (Russel, 1912; Chalmers, 1979):

1. Correlation

First, there must be a correlation between the intervention and the outcome. Correlation is not necessarily causation, it’s true, but correlation is a necessary precondition to proving a causal relationship. Salary cannot be proven to influence job satisfaction, for example, if you find no relationship whatsoever between how much an employee makes and how satisfied they are.

2. Precedence in time

Second, it must be proven that the cause preceded the outcome in time (Dummet & Flew, 1954). For example, no one can claim that a new manager caused an increase in productivity if productivity was already on the rise before the manager was brought in.

Proving temporal precedence requires measuring outcomes at multiple points in time, including prior to enacting a change or introducing an intervention. This is also the reason why longitudinal research studies rank higher in evidence hierarchies than cross-sectional research studies.

3. Ruling out alternatives

The third and final requirement for proving a cause & effect relationship is ruling out alternate explanations of observed results. This requires critical thinking and an intimate knowledge of how an organization functions.

An effective researcher must recognize & control for any outside factors that could lead to the illusion of a cause and effect relationship. If sensible alternative explanations have not been tested & ruled out, then a researcher does not have airtight proof that their intervention caused any changes that were observed.

Basic statistical knowledge to read scientific papers

The Results section of a published scientific paper is by far the most intimidating for a non-scientist to read. However, this section contains essential details on a study’s sample demographics and the magnitude and significance of observed effects, and should not be skipped or skimmed.

You do not need to be a statistical expert to find the information in this section useful and interpretable. You do, however, need to brush up on some basic statistical terminology and concepts:

Basic descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics provide the reader with a snapshot of what a sample’s data looks like. The most commonly provided descriptive statistics are the mean (the statistical average), written as M, and the standard deviation (an estimate of variability), written as SD.

These two statistics can provide you with a sense of what the average person in the sample was like, and how diverse the sample’s scores were. Just remember: a large standard deviation indicates there was a great deal of variation or diversity in scores.